Can the Health Benefits of Fasting be Captured by a Supplement?

(Disclaimer: This blog is not intended as medical advice. Please consult a medical doctor if you are considering taking any new medicines or supplements. Mimio Health has their own disclaimer statements on their product packaging and at the bottom of their home page, which emphasize that their product is not intended to treat or cure disease.)

What is Fasting?

Fasting is generally defined as regular periods of time where you are not eating or drinking beverages other than water. Records of fasting for medical and religious purposes exist as far back as the 5th century BCE and from locations all over the globe. In the time of the ancient Greeks, fasting was believed to prevent evil spirits from entering the body and to promote healing, but nowadays, fasting is gaining popularity as a way to live a healthier lifestyle. In fact, over 30 million Americans practice some form of intermittent fasting.

Why do People Fast?

Many Americans fast to maintain a healthy weight. Intermittent fasting has become popular in recent years due to its relatively easier methods compared to other styles of fasting or dieting. For one, total calorie intake is not limited with intermittent fasting. For another, once the period of food abstinence is over, there are no rules dictating what you should eat. This tends to be much more approachable for most people compared to vague advice such as, “eat a healthy diet” or overly stringent guidelines (e.g., not eating any carbohydrates on a ketogenic diet). Intermittent fasting simply dictates that you refrain from eating for a period of time before resuming eating. There are a few different styles of intermittent fasting. Alternate Day Fasting (ADF), as one might expect, is when you do not eat for an entire day, or consume only about 25% of your energy needs, followed by a day of eating freely. A 5:2 fasting regime is like ADF, but there are 5 days per week of eating freely and 2 days of fasting. The fasting days need not occur consecutively, but it is up to you. Time-restricted eating (TRE) confines eating to a block of 4-8 hours within a day, with fasting taking place the rest of the day (e.g., for 16 hours). Although fasting is usually done for body maintenance, there are many other benefits of fasting for other systems in the body.

What Happens to Your Body When You Fast?

Fasting triggers a survival mechanism in your cells that ultimately makes them more resistant to stress. While your brain may know that your next meal is in 16 hours, your cells perceive an environmental stress and enter a process to get into survival-mode. There are five proposed steps of fasting, which involve fasting for as many as three days at a time. The first stage takes place about 12 hours after the start of fasting and involves your body using up energy stored in the form of glycogen (i.e., sugar). When this source runs out, your cells rely on your reserves of fat. This process is also known as ketosis. The second stage is marked by the production of specific ketones which then initiate processes to reduce inflammation and repair damaged DNA. Stage three occurs within 24 hours and is when autophagy begins. Autophagy is described in more detail below, and it can be achieved during intermittent fasting (i.e., before 24 hours) or through exercise. By 48 hours, growth hormones levels rise, which helps preserve muscle and reduce fat, and is also linked with longevity. By 54 and 72 hours, insulin levels are low, which helps reduce inflammation and make you more insulin sensitive. This is very beneficial, as appropriate insulin sensitivity can help protect against chronic diseases like diabetes and cancer. In the final stage of fasting, blood stem cells begin to regenerate, which is important for your immune system.

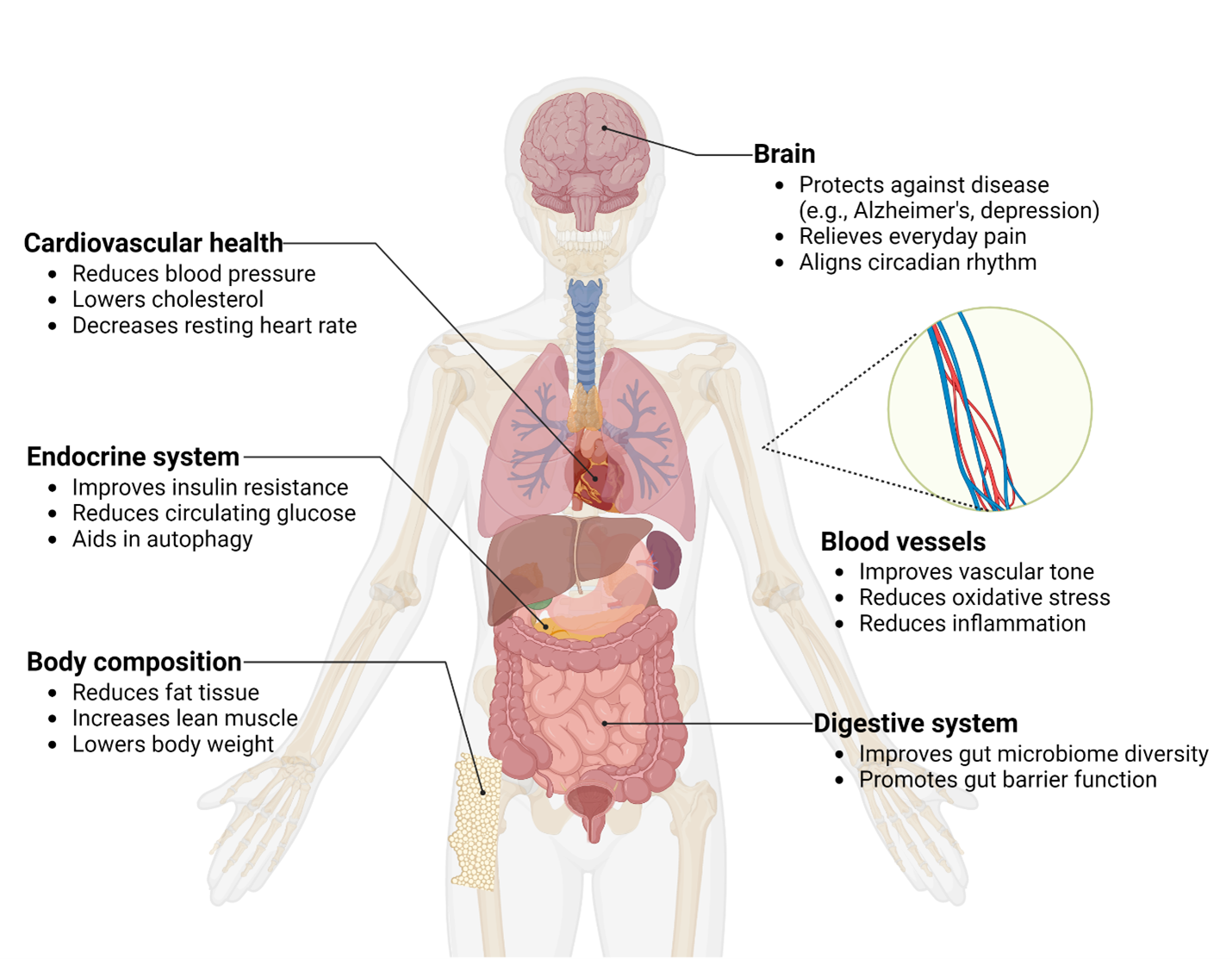

Intermittent fasting is also believed to better align your body systems with its circadian rhythm to improve metabolic health. While the master biological clock of mammals is located in the brain, there are also “clock oscillators” in tissues like the liver, pancreas, fat, muscle, and gut. There are many studies that show when the circadian rhythm is disrupted, there is an increased risk of obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer. Overall, the benefits of fasting range from the molecular level to the organism level. These effects and a few others are summarized in Figure 1. But one of these benefits needs a little more explanation. After all, autophagy isn’t generally a topic of dinner conversation.

What is Autophagy?

Autophagy (aw-TAH-fuh-jee) is the process cells use to break down and recycle old or abnormal proteins and other cytoplasmic materials, like mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum. This housekeeping work is believed to be important for balancing sources of energy for cells to use during periods of stress or starvation. Clearing out the junk frees up space and speeds up cell function. When autophagy takes place, the cytoplasmic materials, including organelles, DNA fragments, proteins, and mitochondria, and packaged into autophagosomes (Figure 2). Autophagosomes are double-membrane units, and there is a receptor on the inner membrane that lets the cell know the materials can be degraded.

After the materials are done being packaged for recycling, the autophagosome fuses with lysosomes, thereby releasing enzymes that break down the original contents. These macromolecules are then transported back to the cell for reuse as building blocks for new proteins, and possibly carbohydrates and lipids (Figure 2). Autophagy in most cell types is triggered by depletions in amino acids, the building blocks of proteins, though each cell may not be able to detect nutrient availability. Some studies suggest that autophagy is regulated by the entire organism, likely through the endocrine system via hormones like insulin.

Autophagy can also destroy bacteria and viruses and therefore plays an important role in supporting a healthy immune system. It is also believed to be key in preventing neurodegeneration, diabetes, and many other types of disease. Autophagy is not a silver bullet, though. For example, there is conflicting evidence about its role in cancer: in some studies, autophagy is shown to suppress tumor growth, while in others, it is thought to supply the nutrients that enable cancer cell growth. As with most processes in the body, a healthy balance is usually what works best.

It is important to note that while fasting can be used as a strategy to maintain a healthy weight, there are certain people for whom fasting poses greater risks than benefits. Diabetic individuals, for example, must maintain proper glucose levels throughout the day, and individuals with disordered eating may not be advised to participate in fasting. For these groups, and those who would like to incorporate the benefits of fasting without changing their diet and lifestyle, Mimio Health may have an exciting solution.

Who is Mimio Health and What are Their Claims?

Mimio Health has developed a supplement that mimics the cellular benefits of fasting without actually having to change anything about when and what you eat (Figure 3). Mimio Health (originally named Innate Biology) was founded in 2023 by Dr. Chris Rhodes, who has a PhD in nutritional biochemistry from the University of California, Davis. Part of his graduate work was conducting years of clinical research on human fasting that served as the basis for starting Mimio. Their formulation contains molecules that are naturally elevated after 36 hours of fasting. These molecules include nicotinamide, oleoylethanolamide, palmitoylethanolamide, and spermidine.

Nicotinamide

Many studies show nicotinamide, a derivative of vitamin B3, is beneficial to cardiovascular health because of its anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anti-thrombotic (i.e., blood clots where you don’t want them) properties. Nicotinamide can be found in meat products like liver, though it is also in mushrooms, algae, and seaweed. After fasting for 36 hours, nicotinamide is 4 times higher than normal. While there are no reports for a recommended daily intake, food safety authorities report safety at dosages up to 270 mg per day. Mimio supplies 500 mg of niacin, which is also known as vitamin B3 and is the generic name of nicotidamide. This amount is 3,175% of the daily recommended value, but because this is a water-soluble molecule, what isn’t used will be excreted.

Oleoylethanolamide

Oleoylethanolamide (OEA) helps control hunger and cravings and is upregulated 2.7 times above baseline after 36 hours of fasting. It is a product of oleic acid, which is a healthy fat believed to play a role in reducing inflammation and oxidative stress. While oleic acid is found in olive, peanut, and sunflower oil, OEA is mostly found in animal products, especially organ meats. Therefore, Mimio’s vegan formula provides a helpful source of OEA for individuals whose diet does not contain meat. While studies show positive metabolic effects when obese subjects were provided doses of 250 mg per day, the Mimio formula provides 300 mg per serving.

Palmitoylethanolamide

Palmitoylethanolamide (PEA) helps cells recover from stress and is 2.4 times more concentrated after fasting for 36 hours. PEA is primarily found in soybeans, peanuts, peas, and black-eyed peas and acts on the immune system, neuronal cells, and the endocannabinoid system to alleviate pain, promote joint health, and improve sleep and recovery. Large-scale clinical trials indicate up to 1200 mg of PEA per day is well-tolerated, and the Mimio daily supplement provides 400 mg, giving our cells a chance to bounce back.

Spermidine

Spermidine is a byproduct when cells break down proteins and is most noted for its role in inducing autophagy, which we know is important for maintaining overall cell health. Spermidine is also found in foods like wheat germ, soy, cheese, miso, and various nuts, seeds, and mushrooms. While nutritional experts recommend an average intake of 30 mg of spermidine per day, it is estimated that the standard American diet only contains about 8 mg per day. The Mimio supplement provides 5 mg of spermidine per serving, which helps cell renewal.

In sum, these molecules each contribute to Mimio’s claims of boosting metabolism and energy levels, improving mood and mental clarity, creating a balanced inflammatory response, relieving everyday aches and pains, and supporting healthy aging, which agree with hundreds of other studies detailing the health benefits of regular fasting.

Conclusion

Clinical trials investigating fasting indicate it can be a helpful way for individuals to lead a healthy lifestyle and potentially reap other therapeutic benefits like reducing inflammation and blood pressure with very few negative side effects. However, the loss of social interaction around food is among the top drawbacks of fasting, and for these individuals, or those that would rather not calorie restrict at any point throughout the day, Mimio offers an attractive alternative: the benefits of fasting without having to change the way you eat.

References

Kerndt, Peter R., et al. "Fasting: the history, pathophysiology and complications." Western Journal of Medicine 137.5 (1982): 379.

“Fasting.” Encyclopædia Britannica, 2019, www.britannica.com/topic/fasting.

IndieBio. “Innate Biology (IndieBio Demo Day 11).” YouTube, 15 July 2021, youtu.be/1BLmoPVYRCk.

Kohok, Shivaani. “Why Is Intermittent Fasting so Popular?” BBC News, 3 June 2019, www.bbc.com/news/health-48478529.

Varady, Krista A., et al. "Clinical application of intermittent fasting for weight loss: progress and future directions." Nature Reviews Endocrinology 18.5 (2022): 309-321.

PhD, Paige Jarreau. “The 5 Stages of Intermittent Fasting.” LIFE Apps, 1 June 2021.

Patterson, Ruth E., et al. "Intermittent fasting and human metabolic health." Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 115.8 (2015): 1203.

“Autophagy.” National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, 2 Feb. 2011, www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/autophagy.

Glick, Danielle, Sandra Barth, and Kay F. Macleod. "Autophagy: cellular and molecular mechanisms." The Journal of pathology 221.1 (2010): 3-12.

“Autophagy.” Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland Clinic, 23 Aug. 2022, my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/24058-autophagy.

Yun, Chul Won, and Sang Hun Lee. "The roles of autophagy in cancer." International journal of molecular sciences 19.11 (2018): 3466.

“Mimio Health.” Mimio Health, www.mimiohealth.com/. Accessed 17 May 2023.

“Science | Mimio Health.” Mimio Health, www.mimiohealth.com/science. Accessed 17 May 2023.

“Ingredient: On Nicotinamide | Mimio Health.” Mimio Health, 22 Mar. 2023, www.mimiohealth.com/blogs/ingredient-nicotinamide.

Chlopicki, S., et al. "1‐Methylnicotinamide (MNA), a primary metabolite of nicotinamide, exerts anti‐thrombotic activity mediated by a cyclooxygenase‐2/prostacyclin pathway." British journal of pharmacology 152.2 (2007): 230-239.

“Niacin Fact Sheet for Health Professionals.” National Institutes of Health Office of Dietary Supplements, National Institutes of Health, 18 Nov. 2022.

“Ingredient: On OEA | Mimio Health.” Mimio Health, 22 Mar. 2023, www.mimiohealth.com/blogs/ingredient-oea.

“Oleic Acid | Definition, Uses, & Structure.” Encyclopædia Britannica, 2019, www.britannica.com/science/oleic-acid.

Payahoo, Laleh, et al. "Oleoylethanolamide supplementation reduces inflammation and oxidative stress in obese people: a clinical trial." Advanced Pharmaceutical Bulletin 8.3 (2018): 479.

“Ingredient: On PEA | Mimio Health.” Mimio Health, 22 Mar. 2023, www.mimiohealth.com/blogs/ingredient-pea.

Clayton, Paul, et al. "Palmitoylethanolamide: a natural compound for health management." International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22.10 (2021): 5305.

Gabrielsson, Linda, Sofia Mattsson, and Christopher J. Fowler. "Palmitoylethanolamide for the treatment of pain: pharmacokinetics, safety and efficacy." British journal of clinical pharmacology 82.4 (2016): 932-942.

“Ingredient: On Spermidine | Mimio Health.” Mimio Health, 22 Mar. 2023, www.mimiohealth.com/blogs/ingredient-spermidine.

Madeo, Frank, et al. "Nutritional aspects of spermidine." Annual review of nutrition 40 (2020): 135-159.

Atiya Ali, Mohamed, et al. "Polyamines in foods: development of a food database." Food & nutrition research 55.1 (2011): 5572.

Longo, Valter D., and Rozalyn M. Anderson. "Nutrition, longevity and disease: From molecular mechanisms to interventions." Cell 185.9 (2022): 1455-1

Heid, Markham. “How Fasting Can—and Can’t—Improve Gut Health.” Time, 23 Sept. 2022.